Net-Zero Roadmap for the ASEAN Steel Industry:

Pathways for Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore

Southeast Asia’s six largest economies (Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore), collectively referred to as the ASEAN-6 in this report, are expanding their steel production capacity to support industrialization and infrastructure growth, with the exception of Singapore. At the same time, all six countries have made climate commitments, including long-term net-zero targets (by 2050 or 2060). Since the steel industry is among the most carbon-intensive industries, decarbonizing this sector will be critical to achieving national and regional climate goals.

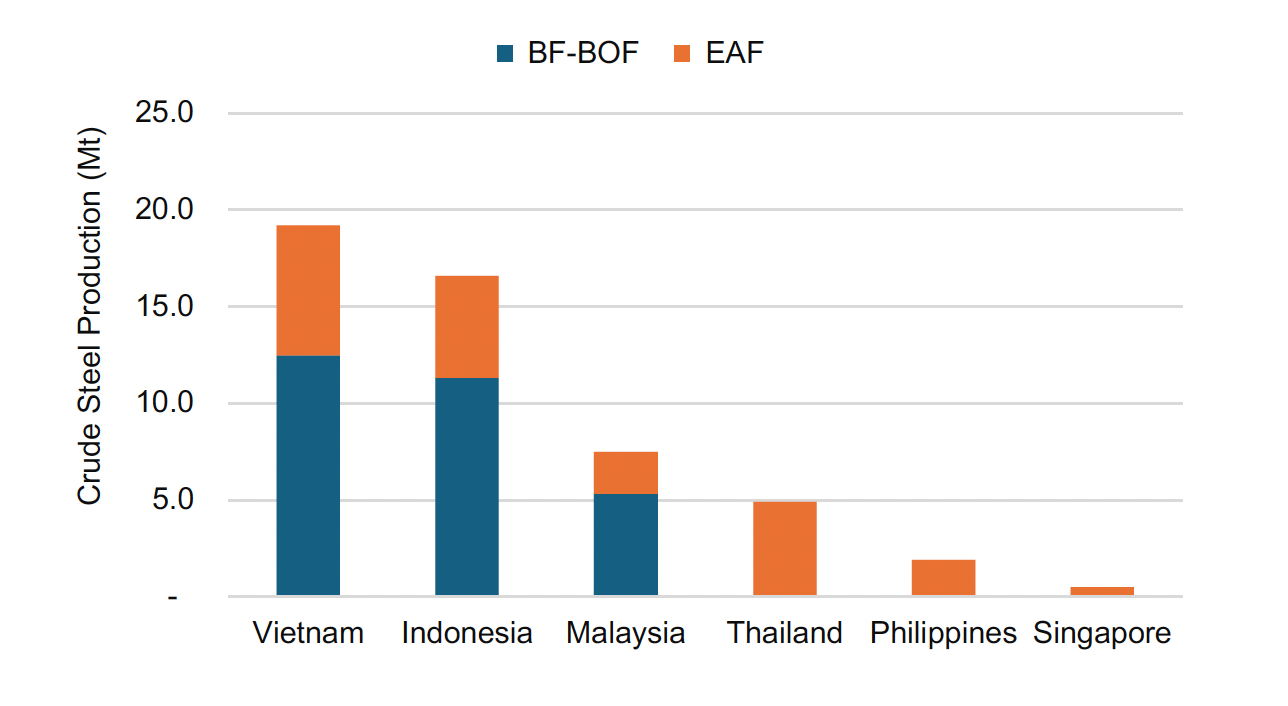

With over 75 million tonnes (Mt) of steel consumption, the combined steel demand of the ASEAN-6 ranks fourth in the world, after China, India, and the U.S. Unlike China, where steel demand is declining, and the U.S., where demand is steady, steel demand in the ASEAN-6 is expected to grow significantly in the coming decades, driven by population growth, urbanization, and ongoing industrial expansion. Vietnam and Indonesia currently lead the region in crude steel output, with Malaysia and Thailand also operating sizable capacities. The Philippines and Singapore have smaller production footprints, though the Philippines is building new primary steelmaking capacity.

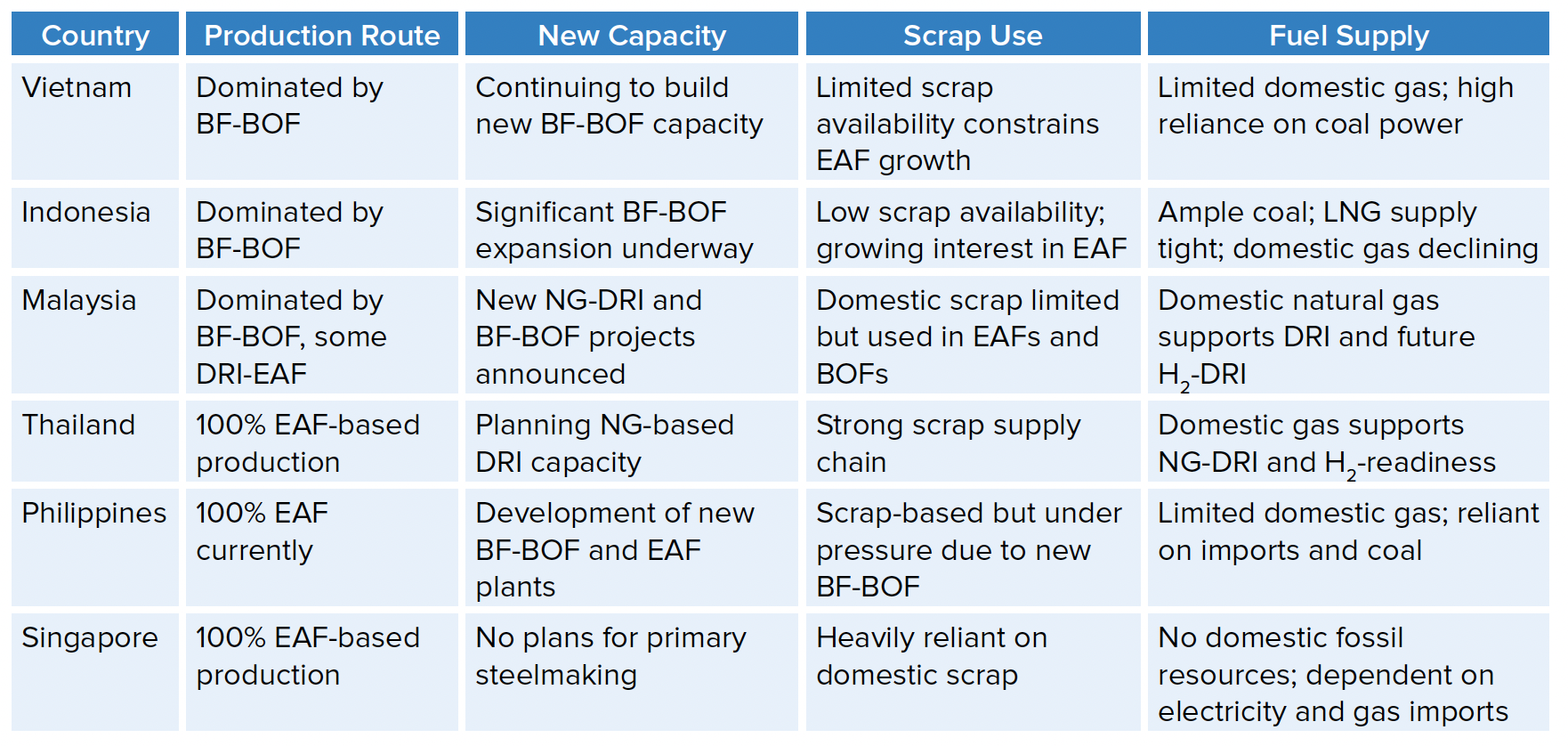

The region operates a mix of production technologies: blast furnace-basic oxygen furnace (BF-BOF), scrap-based electric arc furnace (scrap-EAF), and some direct reduced iron (DRI)-EAF routes. Indonesia, Vietnam, and Malaysia rely primarily on BF-BOF, while Thailand, Singapore, and the Philippines currently produce crude steel entirely through EAF technology (Figure ES1). However, the structure of the steel industry in Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines is expected to change significantly in the next few years as new BF-BOF and natural gas-based DRI (NG-DRI) plants under construction begin operations (see Chapters 5 and 8 for more information).

Figure ES1. Crude steel production in ASEAN-6 countries in 2023 (Source: SEAISI 2024)

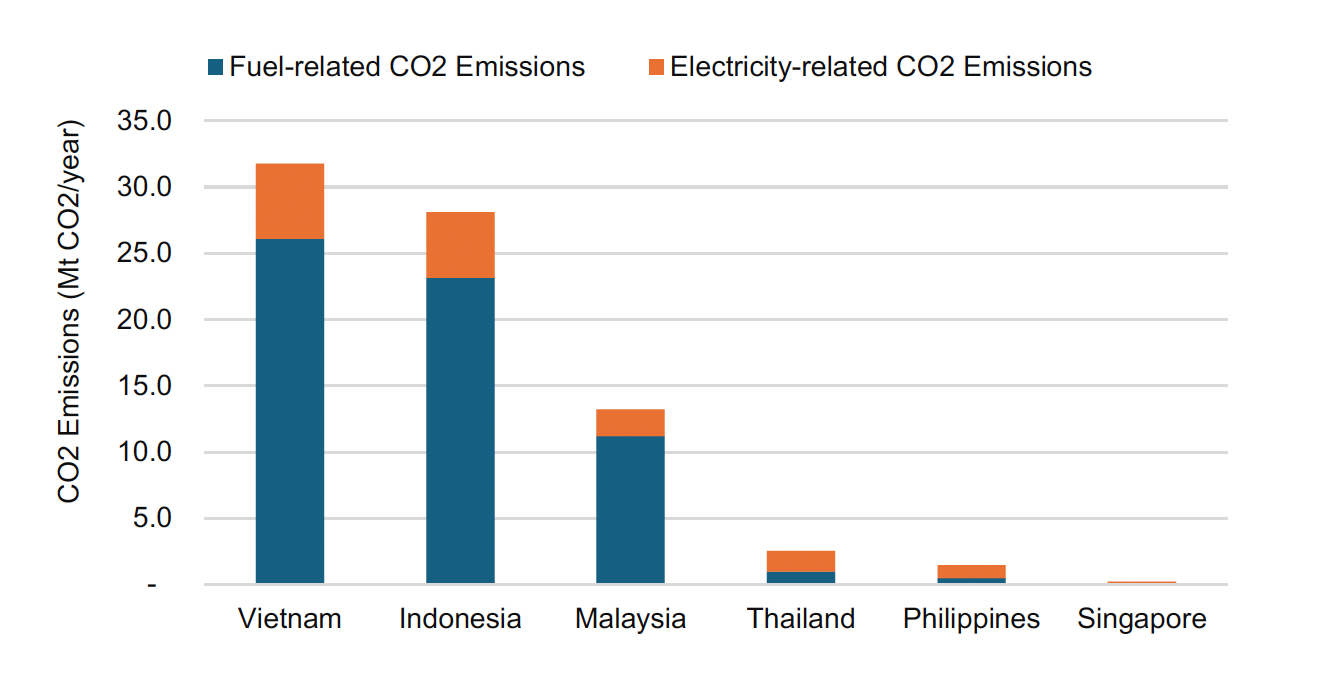

Figure ES2 shows the steel industry’s CO₂ emissions in ASEAN-6 in 2023. Vietnam and Indonesia are by far the largest emitters, with 32 MtCO₂ and 28 MtCO₂ respectively, driven mainly by fuel-related emissions from BF-BOF steel production. Malaysia follows at around 13 MtCO₂, while Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore contribute much smaller amounts, reflecting their smaller steel sectors based on EAF production. Combined, the steel industries of the ASEAN-6 countries emitted over 77 Mt CO₂ in 2023. This is higher than the entire annual CO₂ emissions of Austria (59 Mt CO₂) or Singapore (50 Mt CO₂) in the same year. In fact, these combined emissions exceed the total annual CO₂ emissions of about 160 countries worldwide.

Figure ES2. Annual CO2 emissions of the steel industry in ASEAN-6 in 2023

Note: This study covers only crude steel production facilities (BF-BOF, scrap-EAF, DRI-EAF), including their integrated rolling and finishing lines. Standalone facilities that do not produce crude steel (such as reheating furnaces in rolling mills, cold rolling mills, pipe and tube mills, forging and foundry operations, casting-only facilities, iron foundries, ferroalloy plants, and standalone heat treatment/annealing shops) are not included in this study or in the emissions shown in the figure above.

In this study, we evaluated the energy use and emissions and developed long-term decarbonization pathways of the steel industry in each of ASEAN-6 countries separately using five key decarbonization pillars: 1) material efficiency and demand management; 2) energy efficiency and electrification of heating; 3) fuel switching and cleaner electricity; 4) technology shifts to low-carbon iron and steelmaking; and 5) carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS). We also assessed the contribution of green iron imports (produced through green hydrogen-DRI (H2-DRI) technology in another country and imported by ASEAN-6 countries) on decarbonizing the steel industry in each country. We developed four decarbonization scenarios: Business-as-Usual (BAU), Moderate, Advanced, and Net-Zero, and identified key milestones for 2030-2060.

In 2023, Vietnam’s steel industry relied heavily on coal, which made up 78% of its energy mix due to the dominance of BF-BOF steel production. Electricity accounted for 14%, while natural gas and petroleum products contributed minor shares. The industry emitted 32 Mt of CO₂ in that year, with 80% from fuel use and the rest from electricity. Indonesia showed a similar profile, with 77% of energy use from coal and emissions totaling 28 Mt CO₂ in 2023, about 80% from fuel use. In Malaysia, the steel sector remained dominated by coal, with coking and thermal coal comprising 73% of energy use, while electricity and natural gas accounted for 12% and 13%, respectively. Emissions reached over 13 Mt of CO₂ in 2023, mostly from fuel combustion (Figure ES3).

Thailand’s steel production was fully scrap-EAF-based, so electricity led energy use at 45% of the energy mix, followed by natural gas and petroleum products in 2023. Emissions were evenly split between electricity and fuels, totaling 2.6 Mt of CO₂ in that year. The Philippines also used only EAFs for crude steel production, with electricity at 45% of energy use and petroleum and coal making up the rest. Emissions stood at 1.5 Mt of CO₂, with electricity responsible for two-thirds of the total emissions in 2023. Singapore has only one scrap-EAF plant, with electricity comprising around half of its energy use, followed by natural gas and petroleum products. The country’s steel emissions were just 0.19 Mt of CO₂, with around 60% from electricity and 40% from fuels in 2023. Across ASEAN-6, large BF-BOF-based producers like Vietnam, Indonesia, and Malaysia had significantly higher CO₂ emissions than scrap-EAF-based producers like Thailand, the Philippines, and Singapore.

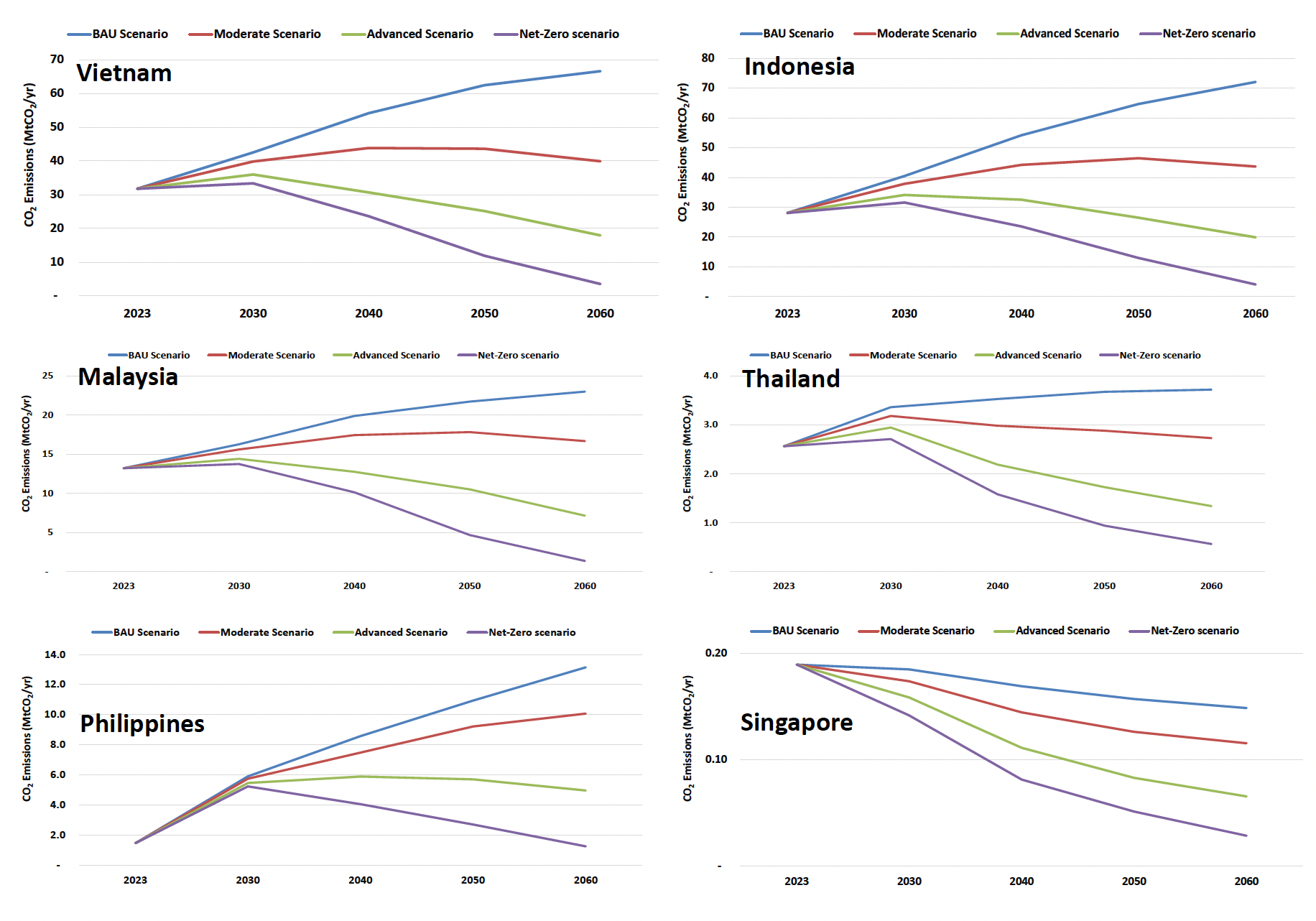

Figure ES3: Total annual CO2 emissions in the steel industry in ASEAN-6 under four decarbonization scenarios, 2023-2060 (Source: this study)

Note: This study covers only crude steel production facilities (BF-BOF, scrap-EAF, DRI-EAF), including their integrated rolling and finishing lines. Standalone facilities that do not produce crude steel are not included in this study or in the emissions shown in the figures above.

Below is a brief summary of decarbonization pathways and the impact of each decarbonization pillar for the iron and steel industry in each of the ASEAN-6 countries based on our analysis.

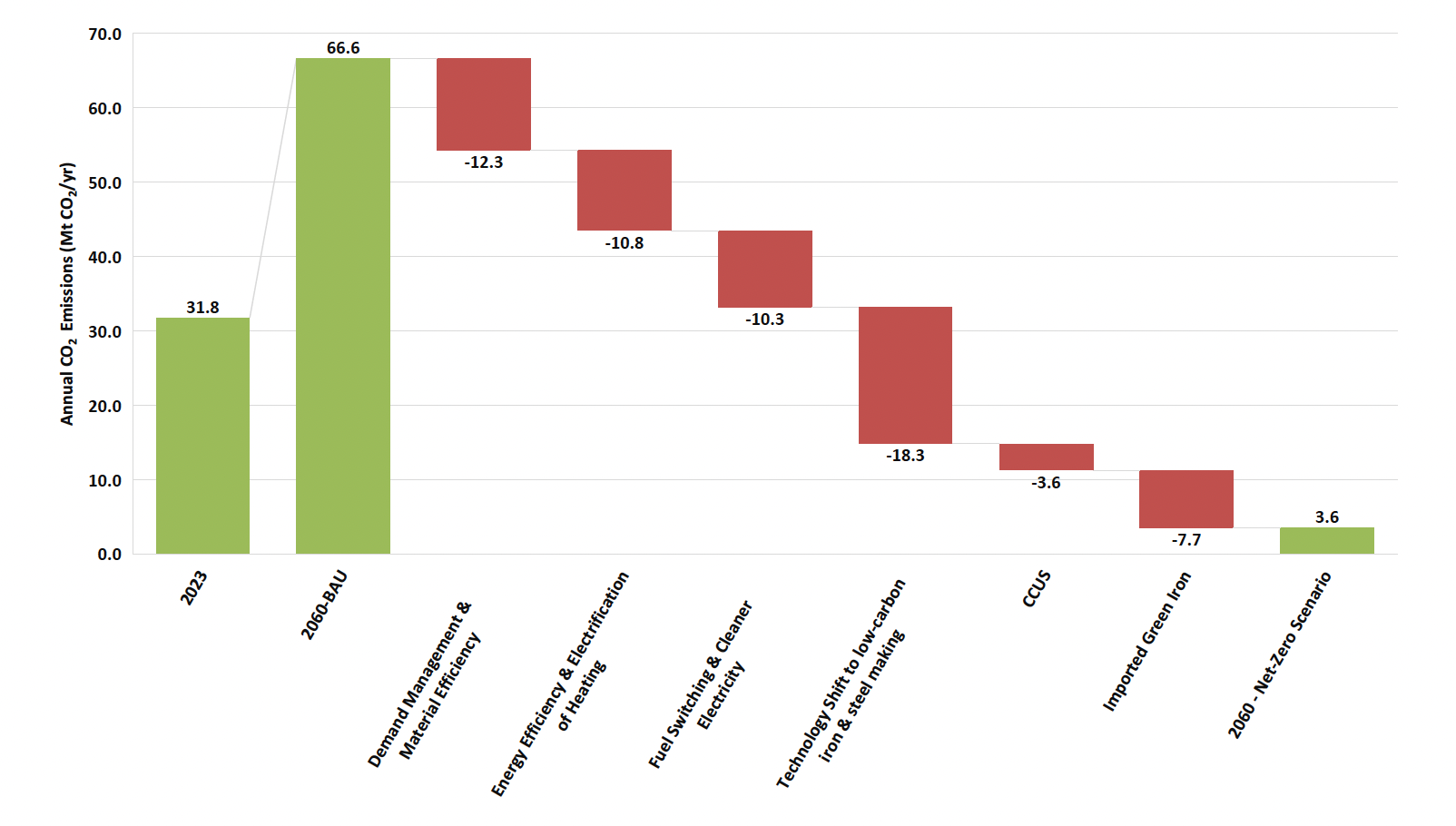

Vietnam

Vietnam’s steel sector emissions are projected to rise to 67 Mt CO₂ by 2060 under the BAU scenario, double the 2023 level, driven by high output growth and limited technology shifts. However, under the Net Zero scenario, emissions fall by 89% relative to 2023, supported by demand management, energy efficiency, cleaner fuels and electricity, and deployment of scrap-EAF, green H2-DRI-EAF, and electrolysis. The technology shift pillar delivers the greatest emissions reductions, driven by the deployment of low-carbon iron and steelmaking technologies such as natural gas-based DRI-EAF, scrap-based EAF, green H2-DRI-EAF, and iron ore electrolysis. Demand-side measures rank as the second most significant contributor. Improvements in energy efficiency and the use of cleaner fuels or electricity each offer a comparable level of emissions reduction. The analysis shows that CCUS plays a smaller role relative to the other mitigation strategies. Additionally, substituting domestic iron production with imported green iron in EAFs reduces emissions by 7.7 Mt CO2 annually by 2060 compared to the BAU scenario.

Indonesia

In Indonesia, steel sector emissions are expected to reach nearly 72 Mt CO₂ by 2060 under BAU, a 160% increase from 2023. The Net Zero scenario reduces emissions by 86% relative to 2023. Technology shifts to low-carbon iron and steelmaking deliver the biggest cuts, followed by similar contributions from material efficiency and demand-side actions, energy efficiency and electrification, and cleaner fuels and electricity. Imported green iron and CCUS play smaller but growing roles after 2040.

Malaysia

Malaysia’s steel emissions are projected to rise 74% to 23 Mt CO₂ by 2060 under BAU. Similar to Vietnam and Indonesia, the Net Zero pathway, enabled by technology shifts to cleaner iron and steelmaking, strong efficiency gains and switching to cleaner fuels and electricity, reduces emissions by 90% from 2023. Green iron imports and CCUS contribute modestly. Reductions in the near term come mostly from demand management and material efficiency, and energy efficiency, while from 2040 onwards, other decarbonization pillars begin to make significant contributions to emissions reduction.

Thailand

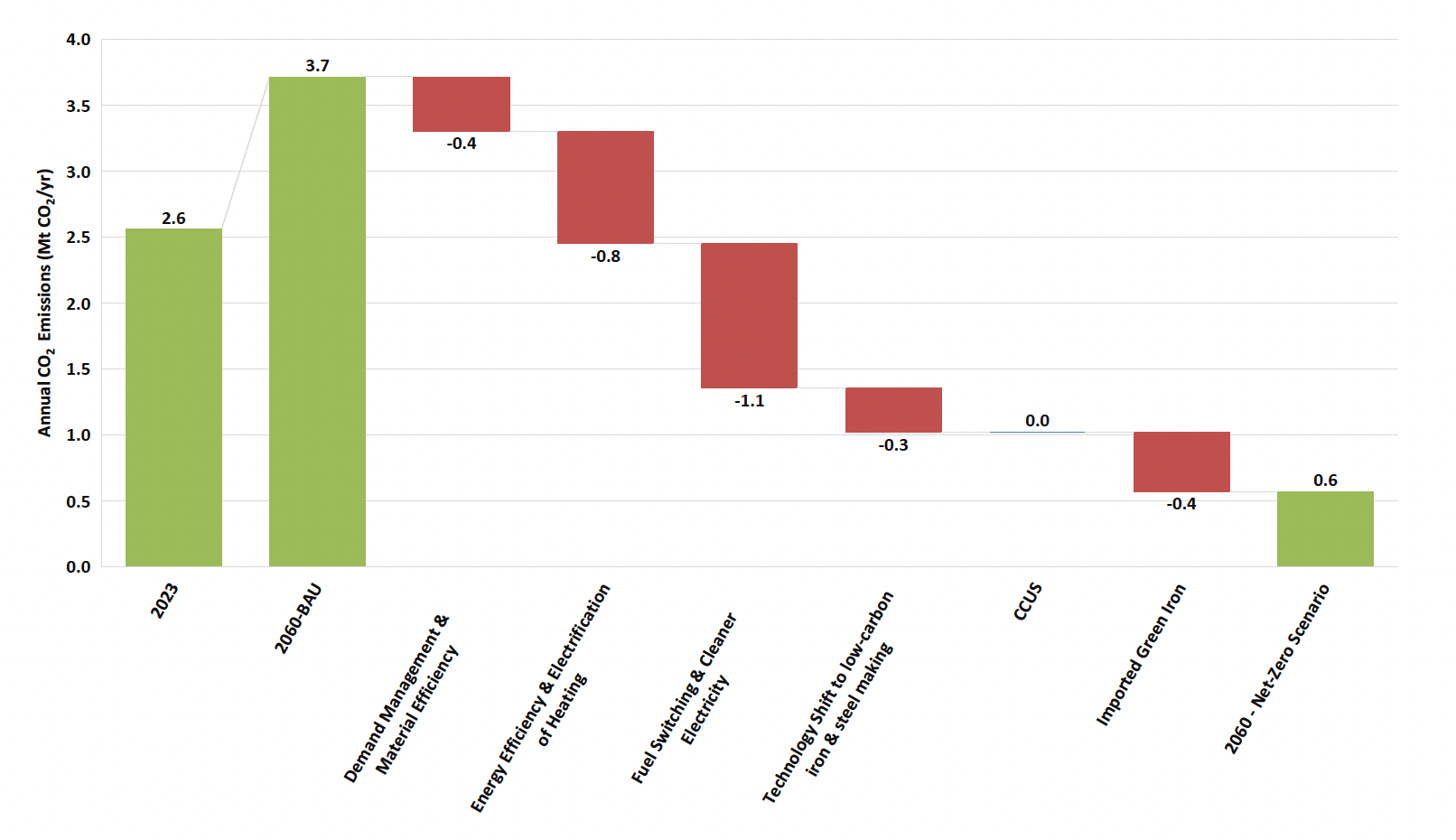

Thailand’s BAU emissions rise to 3.7 Mt CO₂ by 2060, up 45% from 2023. In the Net Zero scenario, emissions fall by 78% relative to 2023 and by 85% relative to BAU in 2060. Since Thailand relies solely on EAF steelmaking and a possible new natural gas-based DRI plant, without any BF-BOF operations, the results differ from those of other countries. Fuel switching and cleaner electricity provide the biggest single reduction (1.1 Mt CO₂), followed by energy efficiency and electrification of heating (0.8 Mt). CCUS has no role in the Net Zero scenario since the potential forthcoming DRI plant in Thailand is expected to transition gradually to 100% green H2-DRI by 2060 under this scenario.

Philippines

The Philippines sees a sharp emissions increase in the short term, jumping from 1.5 Mt CO₂ in 2023 to around 6 Mt by 2030 under BAU due to rapid production growth driven by steel plants under construction that start operating in the next few years. Under BAU, annual emissions reach 13.2 Mt CO₂ in 2060, nearly nine times the 2023 level. The Net Zero scenario limits 2060 emissions to 1.2 Mt, over 90% cut from BAU. Technology shifts to low-carbon iron and steelmaking deliver the biggest cuts, followed by similar contributions from energy efficiency and electrification, and cleaner fuels and electricity. Imported green iron and demand management and material efficiency also play significant roles.

Singapore

Singapore’s steel emissions remain low throughout the period due to limited domestic production. BAU emissions drops by around 25% by 2060, while the Net Zero scenario cuts emissions by 88% by 2060. Emission reductions are mainly from fuel switching and cleaner electricity, followed by energy efficiency and electrification of heating.

Figures ES4 and ES5 illustrate the impact of each decarbonization pillar on CO₂ emissions in the steel industry for Vietnam and Thailand, serving as examples for the ASEAN-6 region. The contribution of each pillar differs across countries, influenced by the structure of their steel industries and other national circumstances. Comparable figures for the remaining countries are presented in Chapter 4.

Figure ES4. Impact of each decarbonization pillar on CO2 emissions of Vietnam’s steel industry, Net Zero scenario relative to BAU (Source: this study)

Figure ES5. Impact of each decarbonization pillar on CO2 emissions of Thailand’s steel industry, Net Zero scenario relative to BAU (Source: this study)

Note: CCUS shows no impact in Thailand since we have assumed that the one DRI plant that will be built in Thailand will gradually shift to 100% green H2, so there is no need for CCS adoption on that DRI plant.

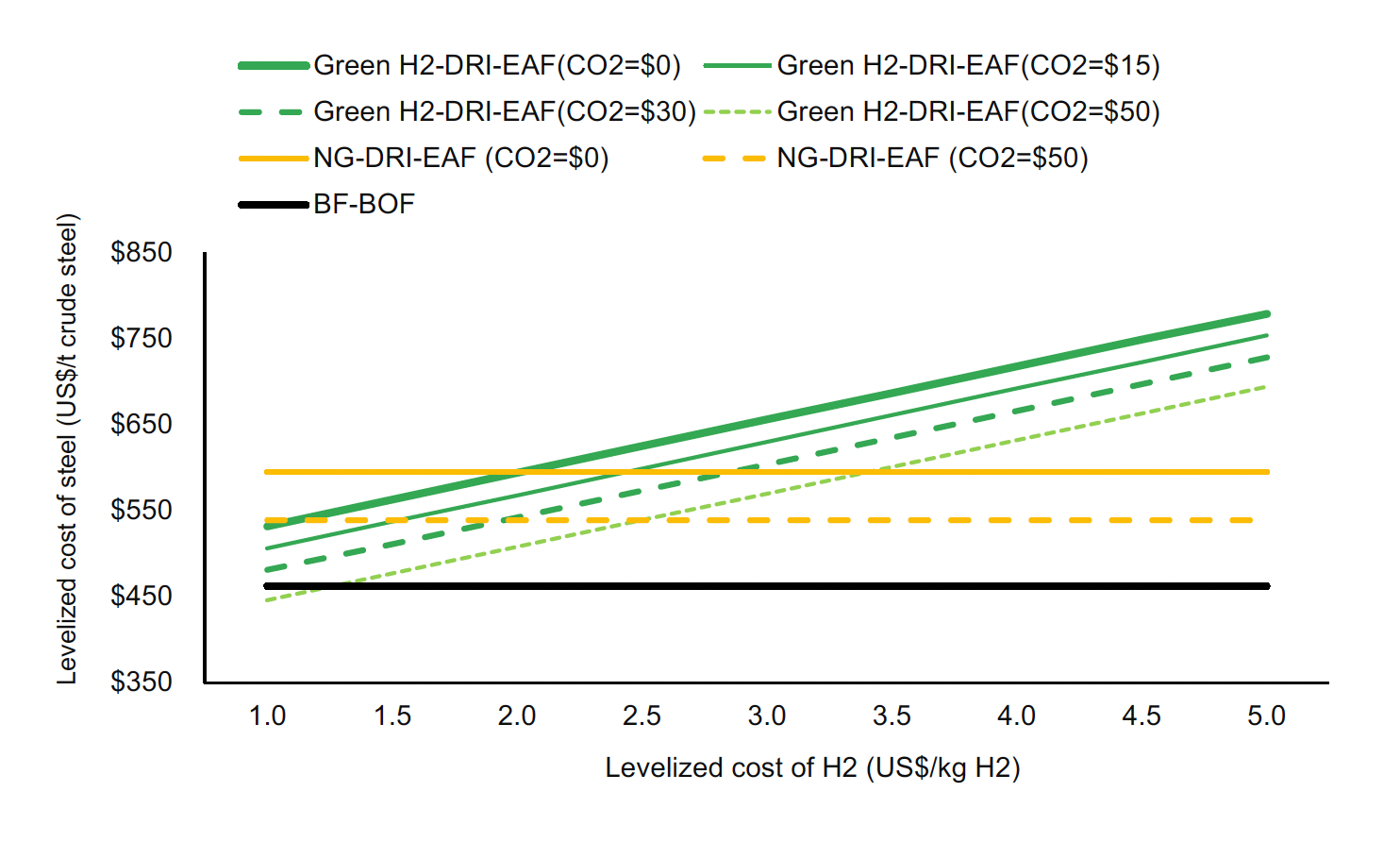

We also analyzed the economic viability of green H₂-DRI-EAF in ASEAN countries by comparing its levelized cost of steel (LCOS) with those of BF-BOF and NG-DRI-EAF routes. Our recent studies find that the LCOS for H₂-DRI-EAF is similar across Southeast Asia’s major steel-producing countries, mainly due to comparable costs for materials, CAPEX, OPEX, and labor. The hydrogen price is the key factor driving LCOS differences. Therefore, this chapter uses Vietnam as a representative case.

Green H₂-DRI-EAF can reduce CO₂ emissions by up to 97% compared to the BF-BOF route. However, even if hydrogen costs fall to $1/kg, this pathway is still projected to be more expensive under current raw material prices, especially because coking and thermal coal prices have dropped sharply in recent years, making BF-BOF more cost-attractive. Still, as hydrogen becomes cheaper due to technology gains and supportive policies, the cost gap or green steel premium should shrink (see Figure ES6). However, when expressed per unit of end-use products, the green steel premium is quite small. With a hydrogen price at $5/kg, the green premium would be around $285 per passenger car and $790 per 50 m² of residential apartment. This suggests that green steel would have little effect on consumer prices. Over time, falling hydrogen costs and carbon pricing mechanisms are expected to improve the competitiveness of green H₂-DRI-EAF steelmaking in ASEAN countries.

Figure ES6. Levelized Cost of Steel with different costs of green H2 at different carbon prices in Vietnam (Source: this study)

Notes: For this analysis, it is assumed that carbon pricing will be applied in the form of credits or allowances for green H2-DRI-EAF plants. Eligible plants would receive carbon credits based on the reduction of their carbon intensity relative to the benchmark set by BF-BOF operations, which can then be traded on the carbon market.

Summary of policy recommendations and action plans:

The steel industry in the six ASEAN countries studied differs in terms of technologies used, feedstock options, and expected growth (Table ES1). While some countries continue to rely heavily on coal-based BF-BOF route or are expanding them, others like Thailand and Singapore have entirely EAF-based steelmaking, with Thailand planning on building one NG-DRI. Malaysia falls in the middle, using a mix of BF-BOF and a small capacity of NG-DRI, with growing interest in NG-DRI for EAF routes. Despite these differences, common trends are emerging across the region. To tailor policy and action plans effectively, we group the ASEAN-6 countries into three categories based on the makeup and outlook of their steel sectors. Below, we outline policy recommendations for each group.

Table ES1. Summary of Key Characteristics of the Steel Industry in ASEAN-6 Countries

Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines:

Governments in Vietnam, Indonesia, and the Philippines should stop approving new BF-BOF steel plants to avoid locking in high-carbon steelmaking assets and instead prioritize low-carbon technologies like EAF and hydrogen-ready DRI. They should also set carbon intensity performance standards for existing facilities and begin planning green hydrogen hubs in key industrial zones. Scrap-EAF steelmaking will play a substantial role in decarbonizing the steel industry in ASEAN countries. However, currently, most ASEAN countries have limited high-quality domestic scrap and depend on costly imports, but local scrap will grow as buildings, infrastructure, and vehicles reach the end of their life. ASEAN governments need to improve scrap collection, set quality standards, and build regional trade systems to secure future EAF supply.

Financial incentives, such as tax credits and concessional loans, should be offered for clean steel investments, alongside co-financing for pilot projects using low-carbon iron and steelmaking technologies. Governments should also create national green steel certification systems, mandate energy audits, phase out fossil fuel subsidies, and simplify corporate renewable procurement frameworks. Meanwhile, in the near- and medium-term, steel companies should set decarbonization targets, invest in scrap-based EAFs, upgrade BF-BOF efficiency, pilot hydrogen-ready DRI, and improve scrap handling. They should engage in certification programs, secure direct renewable procurement, improve material efficiency, and collaborate with buyers to create demand for green steel.

Thailand and Malaysia:

Thailand and Malaysia should steer new investments for primary ironmaking toward hydrogen-ready NG-based DRI-EAF instead of BF-BOF, since both have domestic natural gas supply. This should be supported by financial incentives, shared infrastructure, and updated permitting criteria. Both governments should integrate hydrogen planning into steel development and update national energy plans to align with low-carbon steelmaking. Policies should promote green H2 blending in DRI, renewable energy procurement through power purchase agreements (PPAs), and green public procurement for low-carbon steel. Steel companies, in the near- and medium-term, should plan for hydrogen-ready NG-DRI plants, secure long-term renewable energy contracts, and collaborate on shared DRI and hydrogen infrastructure. They should conduct feasibility studies for green hydrogen use in DRI plants, adopt efficient EAF and DRI technologies, and develop clear decarbonization roadmaps. Companies are also encouraged to help shape policy and technical standards, and invest in digital/AI tools to enhance efficiency and emissions reduction.

Singapore:

Singapore should focus on decarbonizing its electricity supply to lower EAF steel emissions by expanding renewables, imports of clean electricity, and storage. The government should support industrial clean power procurement through structured PPAs. A green steel certification program tied to public procurement can create demand for low-carbon steel, while circular economy policies can reduce steel use in construction. This can be an extension of the Singapore Green Building Council (SGBC) that certifies steel through its broader Singapore SGBP Certification Scheme. The EAF steel plant in Singapore should secure long-term clean electricity contracts and leverage local scrap supply to recycle steel to achieve a local circular economy and reduce scope 3 emissions.

Steel buyers in the ASEAN-6 countries:

Both public and private steel buyers in ASEAN-6 countries can accelerate decarbonization by shifting procurement toward low-carbon steel. Governments should require Environmental Product Declarations (EPDs) in public infrastructure bids and set carbon intensity thresholds in the procurement of steel. Private companies in steel-intensive sectors such as automotive, construction, and machinery should adopt green sourcing policies, commit to future low-carbon steel purchases, and work with certified suppliers. Coordinated buyer alliances and regional ASEAN-6 procurement clubs can create consistent demand signals. Preferential treatment for low-emission suppliers and leveraging indirect influence, like green building codes or export standards, can further push the market toward cleaner steel.

There is significant overcapacity in steel production across ASEAN, which is closely linked to global dynamics for which China plays a central role. Excess production in China has driven greater exports and pressure on regional markets. At the same time, ASEAN producers are installing new capacity. However, current ASEAN steel production capacity already exceeds plausible regional demand growth, meaning there is no urgency for ASEAN countries to commit to new BF-BOF plants and lock in high-carbon technologies for decades. Instead, the steel sector in ASEAN should pause and reassess. Technologies such as DRI and H₂-DRI are expected to become more economically competitive in the 2030s as green hydrogen costs fall and renewable energy capacity expands. By delaying new BF-BOF investments and focusing on lower-carbon routes, ASEAN countries can avoid carbon lock-in, reduce stranded asset risk, and align their steel industries with long-term net-zero objectives.

To read the full report and see the complete results and analysis of this new study, download the full report from the link above.

Interested in data and decarbonization studies on the global steel industry? Check out our list of steel industry publications on this page.

Don't forget to follow us on LinkedIn and X to get the latest about our new blog posts, projects, and publications.